Seabirds-and-Seals Book Review

Written by Local Guide Laurie Goodlad Pottinger(Shetland With Lawrie). Laurie is also one of our very knowledgeable relief crew members.

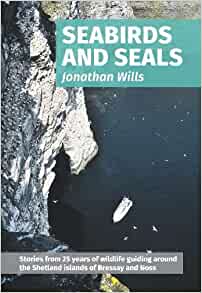

The book that I reviewed is very fitting to an audience of would-be Shetland visitors. Recently published, it was written by Jonathan Wills who operated guided boat tours around Lerwick and Noss for over 20 years. He shares his knowledge and recollections from his time as a tour guide in this lavishly illustrated paperback.

For anyone who knows Jonathan Wills, author of Seabirds and Seals, it will come as no surprise that this book is packed with light-hearted humour, witty anecdotes and is written in an easy, conversational manner. Jonathan describes himself as ‘a ‘half-moother*’, born in Oxford to a Lerwick mother, he has chosen to live in Bressay for most of his life, raising his own family on the island. He established his tour company Seabirds-and-Seals in 1992 with his small, 24ft boat Dunter. Over the years the company grew as increasing visitors took to the water to see the wonders of wildlife just a stone’s throw from Lerwick. With growing interest in boat tours, Jonathan expanded, eventually investing in the Dunter III that he ran until 2015 when he hung up his skipper’s cap and passed the reins over to Brian and Marie Leask who now operate this popular summer tour.

Over the years, Jonathan completed over 4,000 circuits of Bressay and Noss, and this book is borne from the ‘spiel’ that he developed during this time as he guided 39,000 visitors around his little patch of home. He describes his career on Dunter as “a 24-year voyage of some 85,000 miles in all – more than three times around the world without ever being more than three miles from Victoria Pier.”

Unsurprisingly there is the odd political nuance, however, could we expect anything other from the author? The only part that almost raised my hackles was the tongue-in-cheek dig at Scalloway as Shetland’s former capital. As a Scalloway lass, rather than a toonie, I am primed to spot and react to these. Still, thankfully, they were restricted to the introduction where Jonathan discusses how Lerwick grew as a town, eventually overtaking Scalloway as the islands’ economic and legislative powerhouse.

Political nuance aside, his observational eye has given him a deep understanding of nature and the complexities of the wildlife around our shores. His observations on the evolution of the Purple Sandpipers’ migration certainly provided plenty of food for thought and offered an insight I would never have considered otherwise. I was interested in his photos and narrative about Stobister. The picture (above) showed rock debris on top of the cliffs, presumably dumped by the sea. This is interesting as we see a similar example of this on the east side of Mousa where the Great Storm of 1900 laid down a cliff-top storm beach. Perhaps Stobister’s cliff-top beach was formed in the same event – or, when “da oliks cam doon da lum” causing the folk of Stobister to pack up and leave. His grasp of the patterns of life, the birds and other wildlife, right down to the microscopic phytoplanktons’ is truly impressive and have been developed over years of close observation on his many trips around Bressay and Noss.

A few of the descriptions and observations within the book had me laugh-out-loud. A personal favourite was: “Otters have more homes than most MPs.”

These light-hearted and informative descriptions demonstrate Jonathan’s unique storytelling skills, carefully honed over many years guiding visitors. For example, he can take the Holm of Gunnista as a start point and guide the reader through an in-depth tale of Shetland’s past, using the small holm as a launch point into a historic journey of discovery. We learn about how Shetland, at one stage, was wooded before the introduction of grazing animals by our Neolithic forefathers stripped the land bare and, how today, it is now an island of grazing sheep, punctuated by Greylag Geese. He also uses the Holm as the star in the show to explain the complex processes of peat formation. This skill of being able to take a small, otherwise insignificant holm and turn it into a story of evolution and change demonstrates his real talent as an engaging storyteller.

Yet his storytelling runs much deeper, his knowledge is evident, rooted in his ability to succinctly explain complex processes such as the geological makeup of our islands’. Injections of humour add to this narrative, for example, a simple description of how ‘tangles’ at the Setter of Noss can be used to make compost explains the complexities of soil science. Jonathan says, “it’s particularly good [seaweed] when mixed in the compost heap with what comes out of the rear end of a Shetland pony.” It’s clear that his many years at sea – albeit in a radius of only a few miles from Victoria Pier – has given him a deep understanding of all the natural processes involved in our complex ecosystem.

Moving away from Bressay and Noss, Jonathan sets Shetland on the world stage, from the crash of the kelp markets following the Napoleonic Wars’ to the growth of the Dutch fishing industry that arguably funded the expansion of Amsterdam as the economic giant of the world’s trading nations.

These words of praise are not to say that I agreed with everything he said. I did raise an eyebrow (or three) when I read his sweeping statement about Viking colonisation in Shetland in the ninth century. Jonathan says: “Viking pirates laid waste to Shetland and killed or drove away most of its inhabitants.” A bold statement, and one that I’m not sure has any historical – or archaeological – basis, but, it did make me chuckle – and I would love to see the archaeological evidence. He rightly continues, and redeems himself, by acknowledging that “we’re a few PhD theses short of an answer to the mystery”. So perhaps we can allow his imagination to reign in this instance (and … until irrefutable evidence is sought!).

The book itself is filled with fantastic colour photos, detailed maps and illustrations, all interspersed with lively and reflective poetry, giving a real ‘full-dimensional’ view of Bressay and Noss, all recorded from the wheelhouse of three generations of Dunters’. And, as a fisherman’s daughter, it was with a certain sigh of relief that Jonathan commented that in an island community where fishing is the mainstay industry, it is wise not to say too much about the effects of fisheries and aquaculture on the environment. So with political feathers left unruffled, the book closed on a high after an evocative and comprehensive tour of Bressay and Noss – all from the comfort and warmth of my sofa.

Seabirds and Seals covers a few miles of Shetland’s 1,700-mile coastline, and yet it is packed with information about the area – the people, the landscape and the wildlife – as well as placing Shetland on a truly world stage. The book asks questions and throws up different ways of thinking. For example, perhaps Shetland didn’t break away from North America all those million years ago? Perhaps, just maybe, North America broke away from us and went awol? Is America the missing part of the Shetland jigsaw? Stranger things have happened – we need only to look at the current Trump-Johnson administrations to see this. I couldn’t help but marvel at Jonathan’s deep knowledge of the area and, could only imagine how vast our local understanding would be if there were 150-page companions to every part of Shetland’s coastline, presented in such detail.

Seabirds and Seals is a fantastic history of both people, place and, most importantly, the wildlife we share our shores with. So, if you want to find out how the USSR and Mikhail Gorbachev are responsible for the demise of the kittiwake in Shetland, then I suggest you buy Jonathan’s book. I thoroughly enjoyed reading Seabirds and Seals and admire, and thank, Jonathan for the amount of work that has gone into researching this book to share with us.

* A sooth-moother is a local term sometimes used to describe people who move to Shetland from elsewhere. Reference to ‘sooth-moother’ describes how people get to Shetland, via the Sooth Mooth (south mouth) of Lerwick Harbour.